ABOUT STOP PRESS

Stop Press is ISBN Magazine’s guide to happenings in Hong Kong. From art to auctions and from food to fashion, to entertainment, cinema, sport, wine and design, scroll through the best of the city's dynamic cultural offerings. And if your event merits mention in our little book of lifestyle chic, write to us at stoppress@isbn-magazine.com

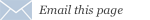

Monet: man of the moment

For a man whose work appears today so art establishment, Claude Monet’s influence on painting was radical and divisive in its day. Monet (1840-1926) urged his friends and peers (which included types like Edouard Manet doing portrait and figure compositions) to abandon formula and get out of their studios, paint en plein air (open air) in front of the ‘motif’. Monet took to the water and had a small boat fitted out as his mobile studio - an effect so dramatic, Manet painted Monet working in his boat, in 1874.

Monet had been influenced by JMW Turner, the British painter whose London seascapes convinced Monet that the effects of light and air combined with water mattered more than practical subject matter. Monet painted in the moment, a technical innovation. As nature evolved by the minute, so Monet said the painter must work fast, capturing light as it was changing. Forget the multi-layered Old Mastery of nature as a finished work, this was pre-photographic shutter speed strokes of the brush, the artist in New-World instantaneousness. And the critics, much like the Establishment, hated it.

In France at that time, the only venue for an artist to gain recognition was the Salon de Paris, an annual and biannual exhibition of the Academie des Beaux-Arts, whose conservative offerings perfectly matched the audience's preconceived notions of the look and purpose of art. Monet and his contemporaries couldn't get their work accepted by the Salon in 1863. (Neither could Manet or Whistler, doubly ironic given that Manet acknowledged his inspiration as coming from the Old Master tradition of Titian, Velazquez and even Goya).

As a result, Monet and friends in 1874 arranged a show at Durand-Ruel, a photographer's studio. One of Monet's pictures - a harbour seen through morning mist - was titled in the catalogue, Impression: sunrise. One of the critics saw the image, and underwhelmed by its ridiculous title, referred to the artists as The Impressionists - it wasn't a compliment; he thought the work unsound from an artistic perspective and more like 'pictures'. He wrote: "What ease in the brushwork. Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more laboured than this seascape." But the label stuck. A satirical magazine of the time labelled them lunatics suffering from collective delusion.

By 1900, at the age of 60, in the same Durand-Ruel gallery, Monet exhibited 22 paintings of his most daring work: the waterlilies in his Giverny garden, into which he’d moved in 1883. Monet had to ask the mayor of Giverny if he could dig a small pond in his garden and install a sluice so he might capture the water from the Epte river flowing alongside it. He grew exotic plants and installed a Japanese bridge inspired by Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Sites in Edo; he also had rare flowers delivered to the garden from Japan through Tamada Hayashi, a Japanese dealer and collector living in Paris. The work was a triumph and the influence of The Impressionists and their once called ‘palette scrapings’ assured.

Claude Monet: The Spirit of Place at the Hong Kong Heritage Museum (part of Le French May 2016 festival in Hong Kong) is the largest exhibition ever devoted to the artist in the city. It features some of his most emblematic paintings, pastels and tapestries from site-specific places in his life; Normandy and Brittany Paris and the Ile-de-France region; London and Venice; and Giverny. Proof that over 70 years, his genius and perseverance ensured universal approval. Monet was a free spirit and much like his work, a force of nature.

Claude Monet: The Spirit of Place. Hong Kong Heritage Museum, May 4 - July 11.

Image: Courtesy the Hong Kong Heritage Museum; Le French May

Monet: man of the moment

For a man whose work appears today so art establishment, Claude Monet’s influence on painting was radical and divisive in its day. Monet (1840-1926) urged his friends and peers (which included types like Edouard Manet doing portrait and figure compositions) to abandon formula and get out of their studios, paint en plein air (open air) in front of the ‘motif’. Monet took to the water and had a small boat fitted out as his mobile studio - an effect so dramatic, Manet painted Monet working in his boat, in 1874.

Monet had been influenced by JMW Turner, the British painter whose London seascapes convinced Monet that the effects of light and air combined with water mattered more than practical subject matter. Monet painted in the moment, a technical innovation. As nature evolved by the minute, so Monet said the painter must work fast, capturing light as it was changing. Forget the multi-layered Old Mastery of nature as a finished work, this was pre-photographic shutter speed strokes of the brush, the artist in New-World instantaneousness. And the critics, much like the Establishment, hated it.

In France at that time, the only venue for an artist to gain recognition was the Salon de Paris, an annual and biannual exhibition of the Academie des Beaux-Arts, whose conservative offerings perfectly matched the audience's preconceived notions of the look and purpose of art. Monet and his contemporaries couldn't get their work accepted by the Salon in 1863. (Neither could Manet or Whistler, doubly ironic given that Manet acknowledged his inspiration as coming from the Old Master tradition of Titian, Velazquez and even Goya).

As a result, Monet and friends in 1874 arranged a show at Durand-Ruel, a photographer's studio. One of Monet's pictures - a harbour seen through morning mist - was titled in the catalogue, Impression: sunrise. One of the critics saw the image, and underwhelmed by its ridiculous title, referred to the artists as The Impressionists - it wasn't a compliment; he thought the work unsound from an artistic perspective and more like 'pictures'. He wrote: "What ease in the brushwork. Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more laboured than this seascape." But the label stuck. A satirical magazine of the time labelled them lunatics suffering from collective delusion.

By 1900, at the age of 60, in the same Durand-Ruel gallery, Monet exhibited 22 paintings of his most daring work: the waterlilies in his Giverny garden, into which he’d moved in 1883. Monet had to ask the mayor of Giverny if he could dig a small pond in his garden and install a sluice so he might capture the water from the Epte river flowing alongside it. He grew exotic plants and installed a Japanese bridge inspired by Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Sites in Edo; he also had rare flowers delivered to the garden from Japan through Tamada Hayashi, a Japanese dealer and collector living in Paris. The work was a triumph and the influence of The Impressionists and their once called ‘palette scrapings’ assured.

Claude Monet: The Spirit of Place at the Hong Kong Heritage Museum (part of Le French May 2016 festival in Hong Kong) is the largest exhibition ever devoted to the artist in the city. It features some of his most emblematic paintings, pastels and tapestries from site-specific places in his life; Normandy and Brittany Paris and the Ile-de-France region; London and Venice; and Giverny. Proof that over 70 years, his genius and perseverance ensured universal approval. Monet was a free spirit and much like his work, a force of nature.

Claude Monet: The Spirit of Place. Hong Kong Heritage Museum, May 4 - July 11.

Image: Courtesy the Hong Kong Heritage Museum; Le French May