ABOUT STOP PRESS

Stop Press is ISBN Magazine’s guide to happenings in Hong Kong. From art to auctions and from food to fashion, to entertainment, cinema, sport, wine and design, scroll through the best of the city's dynamic cultural offerings. And if your event merits mention in our little book of lifestyle chic, write to us at stoppress@isbn-magazine.com

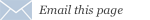

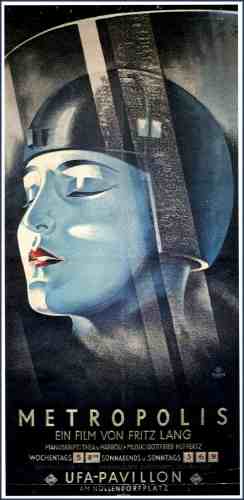

Fritz Lang: Filmopolis of Cinema

Fritz Lang is a cinematic giant. Epics, adventures, spy thrillers, sci-fi or early film noir, he cross-genred at will, with precise aesthetics, weighty themes, technical innovation and singular vision. His standout film - Metropolis - despite its fame, is not cinema's first science-fiction; Jacob Protazanov [Aelita: Queen of Mars, 1924], preceded it, as did Stuart Paton [20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, 1916] and Forest Holger-Madsen [Heaven Ship, 1917], a Danish film about a trip to Mars. Although Metropolis was sci-fi's sharpest rendering in cinema, the sci-fi was a small part of it; the rise of industry and money and man's role in it - masses working as slaves for the ruling elite in a megacity - formed the mainstay. With its art deco urbanscape, futuristic skyline, an obsession with technology's potential to create machines that might soon replace human beings, the film pre-empted the zeitgeist. Machines were not just dead iron, but organs of power. And Metropolis had Maria [Brigitte Helm]. In one of the film's crowning sequences - Maria undergoes a Frankensteinian DNA-sequencing transmission as if by virtual hula hoop, wakes as electronic diva, a female C3P0 fifty years before Star Wars, and dances a veiled routine so Mata Hari-esque and minxy, the corpses of the Seven Deadly Sins rise in unison to play musical instruments in thrall to her exotica. See Maria turn Metropolista; Lang does for cinema, what Mary Shelley did for literature.

Born in 1890 in Vienna, Lang switched from civil engineering to art at university. He visited Africa and Asia, and studied painting in Paris. Injured during the First World War, he joined eminent producer Erich Pommer's studio as a screenwriter, and began directing in 1919. Expressionist visual style dominated his works in the 1920s, including Metropolis, Dr. Mabuse The Gambler, Part I & Part II, The Nibelungen, Part I & Part II. The sound film M shot in 1931 was another of his landmarks. After The Testament of Dr. Mabuse was banned by the Nazi Germany, he left his country and made 23 films in Hollywood, mostly film noir, such as The Big Heat and Human Desire. He died in 1976.

Revisiting Lang - or seeing his work for the first time - is realisation of the debt cinema owes him. His influence is everywhere; from James Bond [Dr No, 1963], Masaki Kobayashi [Kwaidan, 1964], George Lucas [Star Wars,1977] Ridley Scott [Blade Runner, 1982], Peter Greenaway [The Draughtsman's Contract, 1982] Terry Gilliam [Brazil, 1985], Luc Besson [The Fifth Element, 1997], Tom Twyker [Run Lola Run, 1998], Tim Burton [Planet of the Apes, 2001], Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-liang [What Time is it There?, 2001] and even Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar-wai's obsession with time and clocks, which Lang felt exerted sinister control on human lives. Staircases, lifts, maps, circles, polygons, mirrors, arches, geometry and media are other ever-present themes and motifs in Lang's work. There's motion-picture loads of Langian echoes in earlier works too: Leni Riefenstahl [Olympia,1938], F.W. Murnau, his German contemporary, Buster Keaton [Sherlock Jr, 1924], Luis Buňuel [Un Chien Andalou,1929], and much of Hitchcock, via fetishistic motifs - birds, fear of heights - blonde heroines and impeccably dressed leading men.

Destiny [1921] is Lang's first hit. Buňuel said it inspired him to become a filmmaker and Hitchcock told French director Francois Truffaut it impressed him. Lang creates a fantasy allegory with Death granting a woman three chances to save her lover from demise. She experiences three partings in Renaissance Venice, ancient Persia and an imaginary orient in China. The final two conclude with manhunts, setting a precedent for M, Lang's first talkie. Spies [1928] is a stylish thriller so filled with sexual intrigue, high-tech gadgetry and fiendishly slick criminality it still defines the genre 84 years on.

From where did Lang source his inspiration? Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man - inspired in turn by Roman architect Vitruvius - might be a little noted but large presence in Metropolis. Cinematically, he borrowed from Edwin S. Porter [The Great Train Robbery, 1903], Louis Feuillade [Fantômas, 1913], Maurice Torneur [Alias Jimmy Valentine, 1915], Mauritz Stiller [Sir Arne's Treasure, 1919], Ernst Lubitsch [Madame Dubarry, 1919], Rex Ingram [Scaramouche, 1923] and mined Rudolph Valentino films, particularly Four Horseman of the Apocalypse, 1921, also by Ingram. Lang liked good-looking leading men in even better looking suits whose aesthetic withstood whatever plot - and a trip to the Moon - threw at them. [Think Cary Grant in North by Northwest, 1959]. And with Lang, they - and we - get that and more.

The Hong Kong Film Archive is showing a retrospective of sixteen classics by Frtiz Lang until November 18, to be followed by influential German expressionist master, F.W. Murnau, whose 12 surviving films run from December 22 to January 27. Almost all are restored.

Fritz Lang: Filmopolis of Cinema

Fritz Lang is a cinematic giant. Epics, adventures, spy thrillers, sci-fi or early film noir, he cross-genred at will, with precise aesthetics, weighty themes, technical innovation and singular vision. His standout film - Metropolis - despite its fame, is not cinema's first science-fiction; Jacob Protazanov [Aelita: Queen of Mars, 1924], preceded it, as did Stuart Paton [20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, 1916] and Forest Holger-Madsen [Heaven Ship, 1917], a Danish film about a trip to Mars. Although Metropolis was sci-fi's sharpest rendering in cinema, the sci-fi was a small part of it; the rise of industry and money and man's role in it - masses working as slaves for the ruling elite in a megacity - formed the mainstay. With its art deco urbanscape, futuristic skyline, an obsession with technology's potential to create machines that might soon replace human beings, the film pre-empted the zeitgeist. Machines were not just dead iron, but organs of power. And Metropolis had Maria [Brigitte Helm]. In one of the film's crowning sequences - Maria undergoes a Frankensteinian DNA-sequencing transmission as if by virtual hula hoop, wakes as electronic diva, a female C3P0 fifty years before Star Wars, and dances a veiled routine so Mata Hari-esque and minxy, the corpses of the Seven Deadly Sins rise in unison to play musical instruments in thrall to her exotica. See Maria turn Metropolista; Lang does for cinema, what Mary Shelley did for literature.

Born in 1890 in Vienna, Lang switched from civil engineering to art at university. He visited Africa and Asia, and studied painting in Paris. Injured during the First World War, he joined eminent producer Erich Pommer's studio as a screenwriter, and began directing in 1919. Expressionist visual style dominated his works in the 1920s, including Metropolis, Dr. Mabuse The Gambler, Part I & Part II, The Nibelungen, Part I & Part II. The sound film M shot in 1931 was another of his landmarks. After The Testament of Dr. Mabuse was banned by the Nazi Germany, he left his country and made 23 films in Hollywood, mostly film noir, such as The Big Heat and Human Desire. He died in 1976.

Revisiting Lang - or seeing his work for the first time - is realisation of the debt cinema owes him. His influence is everywhere; from James Bond [Dr No, 1963], Masaki Kobayashi [Kwaidan, 1964], George Lucas [Star Wars,1977] Ridley Scott [Blade Runner, 1982], Peter Greenaway [The Draughtsman's Contract, 1982] Terry Gilliam [Brazil, 1985], Luc Besson [The Fifth Element, 1997], Tom Twyker [Run Lola Run, 1998], Tim Burton [Planet of the Apes, 2001], Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-liang [What Time is it There?, 2001] and even Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar-wai's obsession with time and clocks, which Lang felt exerted sinister control on human lives. Staircases, lifts, maps, circles, polygons, mirrors, arches, geometry and media are other ever-present themes and motifs in Lang's work. There's motion-picture loads of Langian echoes in earlier works too: Leni Riefenstahl [Olympia,1938], F.W. Murnau, his German contemporary, Buster Keaton [Sherlock Jr, 1924], Luis Buňuel [Un Chien Andalou,1929], and much of Hitchcock, via fetishistic motifs - birds, fear of heights - blonde heroines and impeccably dressed leading men.

Destiny [1921] is Lang's first hit. Buňuel said it inspired him to become a filmmaker and Hitchcock told French director Francois Truffaut it impressed him. Lang creates a fantasy allegory with Death granting a woman three chances to save her lover from demise. She experiences three partings in Renaissance Venice, ancient Persia and an imaginary orient in China. The final two conclude with manhunts, setting a precedent for M, Lang's first talkie. Spies [1928] is a stylish thriller so filled with sexual intrigue, high-tech gadgetry and fiendishly slick criminality it still defines the genre 84 years on.

From where did Lang source his inspiration? Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man - inspired in turn by Roman architect Vitruvius - might be a little noted but large presence in Metropolis. Cinematically, he borrowed from Edwin S. Porter [The Great Train Robbery, 1903], Louis Feuillade [Fantômas, 1913], Maurice Torneur [Alias Jimmy Valentine, 1915], Mauritz Stiller [Sir Arne's Treasure, 1919], Ernst Lubitsch [Madame Dubarry, 1919], Rex Ingram [Scaramouche, 1923] and mined Rudolph Valentino films, particularly Four Horseman of the Apocalypse, 1921, also by Ingram. Lang liked good-looking leading men in even better looking suits whose aesthetic withstood whatever plot - and a trip to the Moon - threw at them. [Think Cary Grant in North by Northwest, 1959]. And with Lang, they - and we - get that and more.

The Hong Kong Film Archive is showing a retrospective of sixteen classics by Frtiz Lang until November 18, to be followed by influential German expressionist master, F.W. Murnau, whose 12 surviving films run from December 22 to January 27. Almost all are restored.