French couturier, businessman, soldier and diplomat Lucien Lelong had already been decorated with the Croix de Guerre for his heroism in World War I, before opening his fashion house in Paris during the late 1910s. As a contemporary of designers such as Vionnet, Molyneux, Chanel, Lanvin, and Patou, he designed for café society during the 1920s and 1930s. He was not particularly innovative, and chose to concentrate on fine workmanship and fabrication instead. He was, however, always seeking commercial advantage and became the first designer to introduce a lower-priced line - Édition - for less wealthy clients in 1933.

But his 1937 election as president of the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture in Paris proved to be his greatest challenge and contribution to fashion. Lelong became a hero of both wars when he saved the Parisian couture business in the face of Nazi occupation in the early 1940s. Faced with textile rationing imposed by the Nazis and threats to move the high-fashion business to Berlin and Vienna, Lelong negotiated, cajoled, and lied repeatedly to the Germans throughout the occupation, managing to gain exemptions for 12 Parisian couture houses. “One of the first things the Germans did was break into the Syndicate offices and seize all documents pertaining to the French export trade. I told them that la couture was not a transportable industry, such as bricklaying,” he said.

Lelong was credited with saving more than 12,000 workers from deportation into German war industries. "Over a period of four years, we had 14 official conferences with the Germans … at four of them they announced that la couture was to be entirely suppressed, and each time we avoided the catastrophe," he wrote of the experience.

Far from letting the Nazis suppress it, Lelong - an intuitive design scout - liberated the latent talent of young designers and gave them a platform to grow. He employed Christian Dior [1941-46], Pierre Balmain, and Hubert de Givenchy before they became global names. “It was from Lucien Lelong I learned fabrics have personality, as varied as that of a temperamental woman,” wrote Dior of the experience. Dior left in 1947 and set up his own house with the backing of textile manufacturer Marcel Boussac. Dior also lured fashion illustrator Rene Gruau away from Lelong, to give his game-changing “New Look” silhouette a vivid artistic feel.

Exhausted by his war efforts over 20 years, Lelong closed his couture business in 1948 and continued with fragrance instead. He died a decade later in Biarritz. His exquisitely designed perfume bottles are still some of the most covetable on the market today.

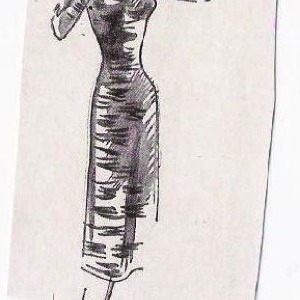

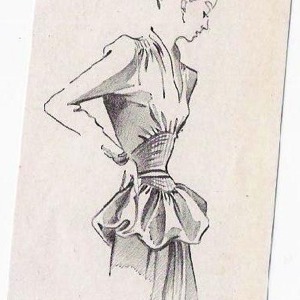

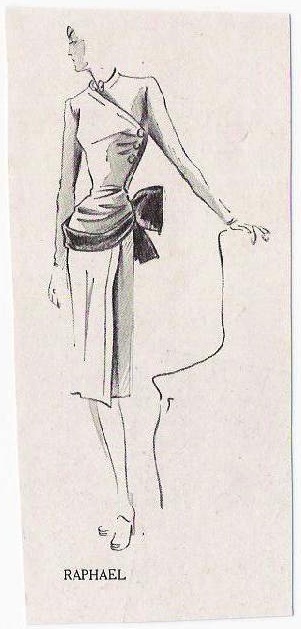

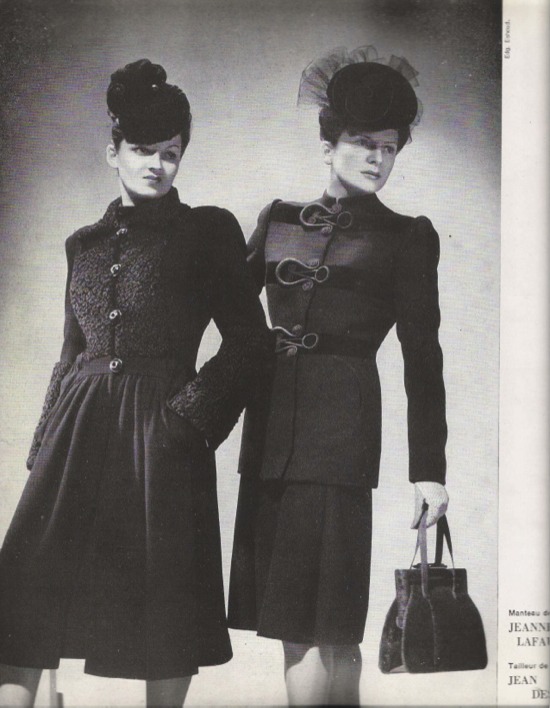

Whatever the immediate fate of high-fashion and its legends both living and of yesteryear, ISBN salutes the heroic Lelong, and those he nurtured, protected and inspired during the occupation. These images, all from 1941, were printed in a special portfolio as part of his – and Paris couture’s - response to Nazi pressure; no matter how bleak the situation in Paris during those dark days, the call to beauty and elegance and dream was the strongest and most passionate urge. Vive Lelong, vive la couture.

But his 1937 election as president of the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture in Paris proved to be his greatest challenge and contribution to fashion. Lelong became a hero of both wars when he saved the Parisian couture business in the face of Nazi occupation in the early 1940s. Faced with textile rationing imposed by the Nazis and threats to move the high-fashion business to Berlin and Vienna, Lelong negotiated, cajoled, and lied repeatedly to the Germans throughout the occupation, managing to gain exemptions for 12 Parisian couture houses. “One of the first things the Germans did was break into the Syndicate offices and seize all documents pertaining to the French export trade. I told them that la couture was not a transportable industry, such as bricklaying,” he said.

Lelong was credited with saving more than 12,000 workers from deportation into German war industries. "Over a period of four years, we had 14 official conferences with the Germans … at four of them they announced that la couture was to be entirely suppressed, and each time we avoided the catastrophe," he wrote of the experience.

Far from letting the Nazis suppress it, Lelong - an intuitive design scout - liberated the latent talent of young designers and gave them a platform to grow. He employed Christian Dior [1941-46], Pierre Balmain, and Hubert de Givenchy before they became global names. “It was from Lucien Lelong I learned fabrics have personality, as varied as that of a temperamental woman,” wrote Dior of the experience. Dior left in 1947 and set up his own house with the backing of textile manufacturer Marcel Boussac. Dior also lured fashion illustrator Rene Gruau away from Lelong, to give his game-changing “New Look” silhouette a vivid artistic feel.

Exhausted by his war efforts over 20 years, Lelong closed his couture business in 1948 and continued with fragrance instead. He died a decade later in Biarritz. His exquisitely designed perfume bottles are still some of the most covetable on the market today.

Whatever the immediate fate of high-fashion and its legends both living and of yesteryear, ISBN salutes the heroic Lelong, and those he nurtured, protected and inspired during the occupation. These images, all from 1941, were printed in a special portfolio as part of his – and Paris couture’s - response to Nazi pressure; no matter how bleak the situation in Paris during those dark days, the call to beauty and elegance and dream was the strongest and most passionate urge. Vive Lelong, vive la couture.

Images de France © ISBN archive

Editor's choice for THE COUTURE ISSUE

Riis Lightning

iScan, uScan, Scandinavia Fashion

Fashion 41

Pop Goes the Easel

Riis Lightning

iScan, uScan, Scandinavia Fashion

Fashion 41

Pop Goes the Easel